An interesting article showed up in my Feed of Interesting Articles this week. It was just a few short paragraphs by a travel writer named Jason Row, but he was commenting on one of the great luminaries of 20th century photography, Henri Cartier-Bresson. Now Cartier-Bresson, you may remember, is justly famous for coining the phrase, and embodying the photographic style, of the decisive moment. This philosophy, though maybe a bit dramatic, nonetheless influenced all of us to some degree. But the article did not examine the idea of photographic moments, decisive or otherwise. Rather it examined, in brief but otherwise revelatory fashion, a lesser-known statement he once made: "Your first 10,000 photographs are your worst."

Mr. Row, it appeared, was taking that 10,000-count somewhat literally, even examining how easily one may approach that figure vis-a-vis film vs digital technologies. I believe Cartier-Bresson intended a more metaphorical reading, at least I hope he did. But if the number itself is merely an arbitrary signpost, to what does it point?

I mean, I clearly remember the refrigerator we had at the studio I first worked and studied at, so many years back. It was packed with, literally, hundreds of feet of film: bricks and pro-packs of 120 film, 100-foot rolls of Tri-X and Ektachrome to bulk-load, and more boxes of sheet film than you could count. There was hardly room for beer, though God knows we tried. So for sheer numbers, 10,000 was hardly daunting.

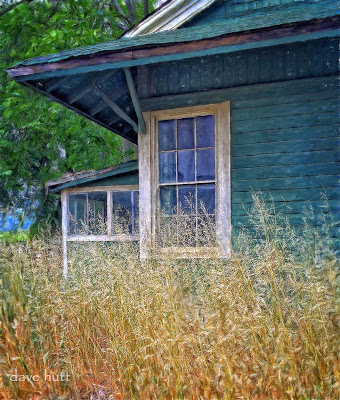

But numbers only represent a larger truth, one hopes. And the truth is, we take our craft seriously, and if it takes a lot of practice to improve -- as surely it does in any worthwhile endeavor -- then let's keep counting. You're first 10,000 anything are not your worst, but they are the signposts on your path that keep pointing ahead. You can be proud of the work you've produced so far without being satisfied. I, for one, have not yet taken my best photograph. Might be the next one. Might be the one after that.

But who's counting?