I don't think I've ever enthusiastically embraced the notion that less is more. Not that I'm given to excess, mind you, at least not terribly often. I don't care for images that are cluttered or poorly arranged either, but the thought that empty space could somehow draw out of the viewer a range of emotions was, shall I say, unsupported. I just don't buy it.

And yet, and yet..........

I spent the better part of this week examining just those very minimalist photographs at the urging of a colleague back east, and could hardly draw my eyes away from them. Hengki Koentjoro, for example, is an Indonesian photographer whose work just blew me away (google him.) So I went through my usual gallery sites with a more refined minimalist eye, and came away impressed. A changed man? At my age, no. But one who came to some revelations about what we've been doing -- or should have been doing --all along.

And it only makes sense. After all, if you think about it, photography is more about what you leave out than what you put in. It's always been that way, we just have a hard time reflecting on it because we're usually in such a darn big hurry. When you bring the camera up to your eyes, you pretty much choke off 99% of the universe in the process. That's not a bad thing, of course; it's the very nature of the art. You just have to slow it down a notch.

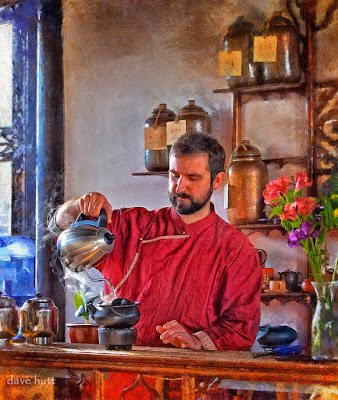

So the task I set for myself was to go out and shoot with a maximalist heart and a minimalist eye. And no, it wasn't that I was going to purposely take "minimalist" photographs; such an objective will surely send you down the wrong path. I take pictures the way I take pictures, but I tried instead to be consciously aware of the elements around me that I was leaving out, and that, as Frost might say, has made all the difference.

Obviously haven't mastered that last part.